Are People with Aspergers Smart: IQ, Strengths, and Gaps

January 26, 2026 | By Leo Sinclair

When you think of Asperger’s Syndrome, popular media might bring to mind characters like Sheldon Cooper or Rain Man—awkward geniuses with near-supernatural intellects. This stereotype often leaves people wondering: are people with aspergers smart in real life, or is this just a Hollywood myth?

In real life, intelligence on the spectrum is more nuanced. You might see strong abilities in one area and real struggles in another—and wonder how both can be true. This guide explains how autism and IQ relate, why “spiky” skills are common, and what you can do with that insight. If you want a gentle starting point, you can explore our Aspie Quiz for a private, educational overview.

What IQ Really Looks Like in Asperger’s and ASD Level 1

A common question is whether everyone on the spectrum is a hidden genius. While the idea is compelling, the statistical reality is more grounded. Are people with aspergers generally smarter than the average person? Not necessarily “smarter” in every way—but the distribution of skills can look different.

Many people who identify with the Asperger’s profile (often described today as ASD Level 1) have average to above-average intelligence. The key point is that “smart” is not one single trait. IQ is one lens, but it does not capture all the ways a brain can work well.

The IQ Distribution Curve: Fact vs. Fiction

In the general population, IQ scores often follow a bell curve. For those with Asperger’s traits, the overall picture is often still wide and varied, but many individuals fall in the average range.

- Average range: Many score within the typical IQ range (about 85–115).

- Above average: Some score in the “superior” range (120+).

- Uneven sub-scores: Even with an average overall score, sub-scores (like verbal reasoning or pattern logic) may be unusually high.

Why Savant Syndrome Is Rare (But Real)

“Savant syndrome” is often confused with Asperger’s. Some estimates are frequently cited in popular writing, but rates vary by definition and study, and most autistic people are not savants.

- The myth: Every autistic person can calculate dates or memorize huge lists instantly.

- The reality: Many people have splinter skills (specific strengths) rather than savant-level abilities.

- The takeaway: You don’t need savant skills to be smart. “Aspie” intelligence can be valid and valuable without being extreme.

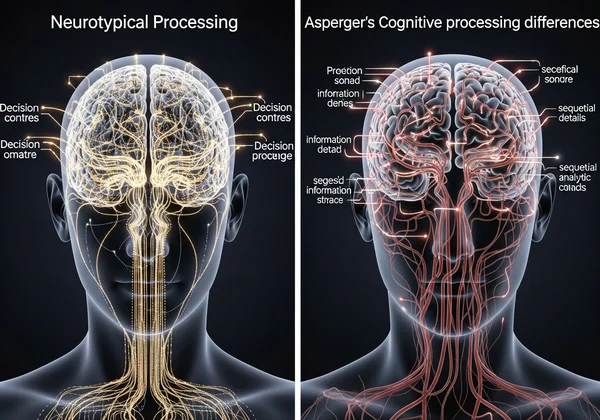

Autism and Intelligence: Why Thinking Can Feel Different

To understand why people with aspergers are smart in unique ways, it helps to look at how information is processed. It isn’t always about processing more—it can be about processing it differently.

Bottom-Up vs. Top-Down Thinking

Many neurotypical brains lean on “top-down” processing: they grasp the big picture first and fill in details later.

- The Asperger brain: Often leans “bottom-up.” Details come first, and the big picture is built from facts.

- The result: This can reduce snap assumptions and improve accuracy, but it may take longer to catch the vague “gist” of a situation.

The Power of Systemizing

Another common pattern is systemizing—the drive to analyze and build systems.

- If-then logic: You may naturally look for rules: “If I do X, Y happens.”

- Comfort in patterns: That’s why coding, math, music theory, or taxonomy can feel “safe.”

- Deep dives: Systemizing can fuel intense learning and mastery in specific interests.

5 Common Cognitive Strengths You May Notice

The stereotype that all autistic people are math whizzes is limiting. Cognitive strengths associated with Asperger’s traits can show up in many fields—from art to engineering to language.

Hyper-Focus and Flow States

Hyper-focus can look like “getting stuck,” but it can also be a superpower.

- What it is: Intense concentration for long stretches, sometimes ignoring hunger or fatigue.

- Why it helps: It supports deep work and rapid skill-building when the task fits your interests.

Exceptional Pattern Recognition

You might notice things others miss.

- Visual patterns: Spotting a typo in a dense document or a small bug in code.

- Behavior patterns: Noticing consistent habits in people over time.

- Logic patterns: Connecting facts that seem unrelated to others.

Unbiased Logic and Honesty

Many autistic people prioritize truth over social comfort.

- Directness: Less “sugar-coating,” more clarity.

- Objectivity: Decisions may be less shaped by peer pressure.

- Integrity: A strong sense of fairness and rules.

Interactive Element: Strength Checklist

Do any of these feel familiar?

- I notice small changes in my environment that others miss.

- When I’m interested in a topic, I can read about it for hours.

- I feel calm organizing things by category, color, or size.

- I prefer written instructions because they feel clearer.

- People say I’m “too honest” or “blunt.”

If you checked three or more, your mind may lean toward systemizing. If you want a structured way to explore this, you can try the Aspie Quiz online test to see how your profile compares across different traits.

Why Some “Easy” Things Are Hard

This is the paradox many people struggle with: “If I’m smart, why is this simple thing so hard?” A common explanation is the spiky profile—sharp strengths in some areas and real gaps in others.

Understanding the Spiky Skill Set

A person might score very high in vocabulary or logic, but lower in executive function (planning, starting tasks, switching tasks).

- The challenge: Others see the “peak” and assume all abilities match it.

- The reality: Being book-smart but struggling socially (or practically) can be a real neurological mismatch—not laziness or a character flaw.

Cognitive Empathy vs. Affective Empathy

Another confusion involves empathy.

- Cognitive empathy: Intuitively “reading the room” can be harder.

- Affective empathy: Feeling care and compassion can be strong.

- What this means: You may care deeply, but miss subtle signals until someone says them out loud.

Living Smart: 3 Strategies to Support Your Valleys

A spiky profile often needs custom strategies, not generic advice. Here are three practical approaches that use structure and planning to reduce daily friction.

Energy Management (Spoon Theory)

High intelligence doesn’t mean infinite energy. Social demands and sensory load can drain you faster.

- Strategy: Treat energy like a budget. Don’t stack high-drain tasks back-to-back.

- Action step: Add a 30-minute “recovery block” after taxing activities to decompress (quiet time, a special interest, a short walk).

Scripting for Social Friction

If social guessing is hard, use your systemizing strengths.

- Strategy: Write simple scripts for repeat situations.

- Action step: If small talk is hard, memorize three “safe” questions:

- “How was your weekend?”

- “What are you working on lately?”

- “Have you watched anything good recently?”

Outsourcing Executive Function

Willpower is unreliable when a task hits a “valley.”

- Strategy: Use external tools as scaffolding.

- Action step: Break tasks into tiny checklists and use calendar reminders (even for small steps). Example:

- Open laptop

- Open document

- Write the title

- Write one bullet point

Self-Discovery in Adults: Safer Next Steps

Understanding your patterns is a step toward self-acceptance. Instead of forcing yourself into a “neurotypical mold,” you can build around your peaks and support your valleys.

Many adults feel “broken” because they judge themselves by standard expectations. Reframing your traits can reduce shame:

- “Bad at people” → “logic-first”

- “Obsessive” → “detail-driven”

- “Too intense” → “deep focus when interested”

When to Consider Professional Support

Self-exploration can be helpful, but it has limits. Consider seeking a qualified professional (psychologist, psychiatrist, or autism-informed clinician) if:

- You feel persistently overwhelmed, depressed, or anxious.

- Daily life is breaking down (work, school, relationships, self-care).

- You’re experiencing burnout, shutdowns, or severe sensory distress.

- You want help with accommodations or an official assessment for practical support.

- You have thoughts of self-harm, or feel unsafe—if so, seek urgent local help right away.

Note: This article is for education and self-understanding. It is not medical advice and cannot diagnose you.

Conclusion: Embracing Your Unique Intelligence

So, are people with aspergers smart? Many are—but often in ways that don’t match a single “IQ stereotype.” Intelligence can be deep, focused, detail-driven, and uneven across skills. That doesn’t make it less real.

If you’re starting to recognize these patterns in yourself, the next step is not to force a label—it’s to understand your profile and build supportive systems around it. If you want a structured, private way to reflect, you can explore the Aspie Quiz and use the results as a starting point for learning and self-advocacy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the smart autism usually called?

Historically, many people used Asperger’s Syndrome. Today, in clinical terms, it is typically described as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), often aligned with ASD Level 1 (depending on support needs). Many people still use “Asperger’s” as an identity or shorthand, even though medical language has shifted.

Are there famous people or geniuses with Asperger's?

We cannot diagnose public figures we don’t clinically assess. Some people publicly describe themselves as autistic or as having Asperger’s traits, and there is also speculation about historical innovators. It’s best to treat these examples as cultural discussion—not proof of diagnosis.

Is high IQ required for an Asperger's diagnosis?

No. High IQ is not required. However, the Asperger’s profile historically implied no intellectual disability and typical language development. Intelligence can still vary widely from person to person.

Can you have Asperger's and be average in school?

Yes. School performance depends on organization, sensory environment, motivation, and social demands—not IQ alone. Someone can be very strong in one subject and struggle in others due to executive function, burnout, or classroom stress.